Coffee making requires a lot of tinkering when trying to find the perfect flavour for your brew. You can spend so much time going in circles trying to figure out how to replicate your latest “eureka” brew, and often it proves incredibly difficult to recreate those flavours. It almost feels like if the stars don’t perfectly align, with a well timed solar-flare to further increase your TDS*, then you have no chance of finding coffee-nirvana.

In espresso nomenclature, the perfect shot is commonly known as the “God-shot”. But getting to that point, and then reproducing that event, takes time and understanding of the multitude of variables that need to be controlled when preparing coffee.

To those just starting to wet their toes into new brewing methods, new toys, and indeed new coffee, the coffee itself almost seems like an afterthought, especially when you’re looking at the different equipment needed to prepare your brews.

It’s really easy to get caught up in how you brew your coffee with the huge amount of different methods available, that we can forget what we are actually brewing. Coffee itself is, perhaps unsurprisingly, the most important variable we can control. The best part? It’s often the easiest.

Coffee goes through an interesting journey from seed to drink, and within that journey another huge amount of variables are in play, but as the end consumer we often don’t need to worry about that, so I won’t cover them here. What I will cover are the three biggest factors you can decide on when buying coffee.

The basics of coffee: Age, roast-level, origin

First, I am going to assume that we are always controlling the most important variable when it comes to buying coffee: that we are sourcing our beans from a reputable roaster. What do I mean by reputable? They are transparent about their sourcing, their process, and their product. Coffee is about celebrating the entire supply chain, and being able to attribute that high quality from the start to the end of it.

Why are these things important? Because those who partake in the industry with transparency are working to further the industry as a whole, and often that commitment is translated into the quality of the end product.

They aren’t in it to take the most well produced coffee and roast away all evidence of where it came from, but instead are bringing the origin of the coffee to the forefront, perpetuating an increase in demand for that coffee, and therefore improving the livelihood of the producer.

With that taken care of, we only need to consider a few more things, and even then, the majority of those things are directed by your personal preference. The major variables are age, roast-level, and origin. These are essentially in order, as if one isn’t satisfied, then the next step can’t truly be evaluated of its own accord.

(I’ve also purposefully left out the processing of the green coffee, as its too overwhelming for those just entering into the coffee world.)

Age: When does coffee go stale?

If you can’t find the “Roasted on” date on a bag of coffee, then I’d tend to steer clear. Often, especially in supermarkets or from roasters that are breaking into far bigger commercial quantities, the “Roasted on” date is missing, instead you will find a “Best before” date, the same as almost any other product on the shelves.

So how do you know what date to choose? The fresher the better, but only when we consider how long we want our beans to last. I tend to buy beans that are 3-5 days post-roast at the most, because I will be drinking them straight away, and a 250g bag will last anywhere from ten to twenty days in our house.

Beans can be “too fresh”. If you drink good coffee that is well roasted on the same day, you’ll find a lack of discernible “greatness” coming from your brew. Coffee needs time to rest, as you’re trying to find a balance between the release of CO2 and the loss of aromatics from the bean.

Good rule of thumb? Light-roasted coffees should be good to start drinking by day five post-roast.

Darker roast? Start a bit earlier. Often dark-roasted coffee will develop more oils on the beans themselves, and oils can go rancid over time.

How long will the beans last? Once we start to pass the one-month mark, then coffee starts to lose a lot of aromatics and has released a large amount of its CO2, resulting in flat tasting coffee. Not only that, if it was a darker roast, then coffee oils have long been released and will be going rancid. Not tasty.

That being said, I’ve had coffee eight weeks after roasting that was still completely drinkable, just not outstanding. I am a proponent of not wasting coffee however, given how much energy goes into creating it. Your model may vary!

Can you store beans for longer? Yep! You can freeze them which will assist in keeping them for longer, but even easier is to just stagger your purchases accordingly.

There are a HUGE amount of variables on the topic of freshness in coffee and if you want to learn a lot more science-stuff about this topic, then check out this awesome podcast from the Specialty Coffee Association.

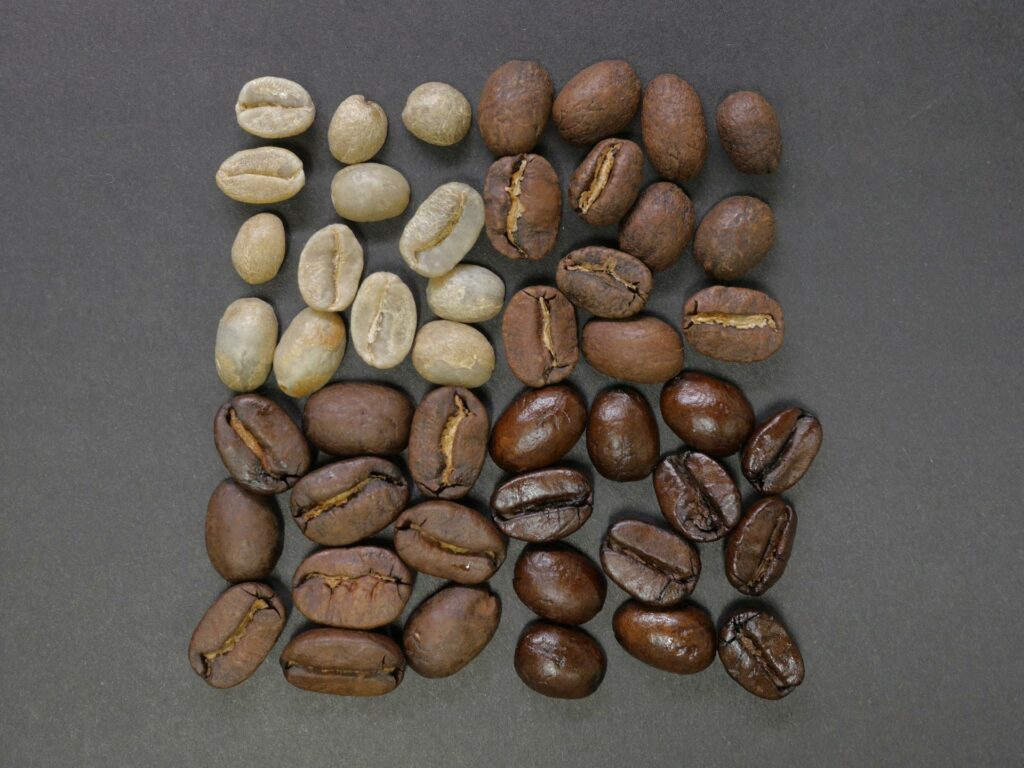

Roast level: Light-roast vs dark-roast

This one is easier to nail down. Want a more fruity, acidic, and brighter coffee experience? Find a lighter roast. Want more of that “coffee” flavour? Find a darker roast. Let’s take a brief look at what’s happening with these two sides.

Lighter roasts are inherently coupled with the origin flavours of a coffee, meaning the flavours that are discernible based on type of coffee itself and where it was grown (commonly known as terroir).

Ever heard of people saying their coffee tastes like blueberry? This isn’t flavour being added, it is from well-roasted coffee drawing out the flavour profile of that specific coffee’s origin. If you’re looking to explore the world of coffee, then aim for light roasts and keep choosing new origins for your coffee (more on that below).

Can a coffee be too lightly roasted? Absolutely, and this is considered a roast defect. Common too-light roast defects are flavours such as “grassiness”, “vegetative”, “herbaceous”. If it feels like you’re a horse chewing hay, then your beans are too light.

Darker roasted coffee produces more of the “roasted” flavour profile. This is attributed to the roasting process itself, with flavours such as “cereal”, “burnt”, and “tobacco” often beginning to show. As darker roasting occurs, those favourable origin flavours mentioned above start to be masked by the roast-level, meaning we lose the flavours more attributable to that specific coffee.

So what should you look for when buying a new bag? Roasters often describe their coffees in similar but sometimes unfortunately different ways. However, the majority industry has pretty cohesively moved to describing roast levels in terms of brew method.

“Filter” coffee is often going to be far lighter than “Espresso” roasted coffee. Does that mean you shouldn’t use that type of roast for a different brew method? No! Try it out, you might find that you love really light espresso (I certainly do) or a really dark-roasted filter brew.

Other ways of describing roast level are a 1-5 scale, or the more legacy “Cinnamon” to “French” roast, but that has fallen behind in current coffee circles because it’s unapproachable for… well anyone. What the heck is a City+ roast when compared to a Full City?

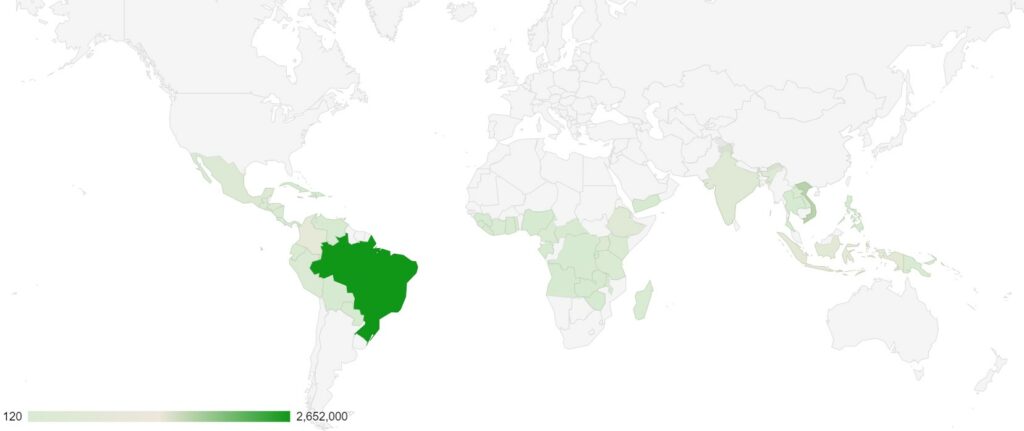

Origin: The regional profile of the coffee

As we mentioned before, the origin of a coffee is the terroir, the characteristics of the coffee based on the environment where it was produced. Additionally, to be able to extract those flavours and showcase them in your coffee, then the roast level needs to be on the lighter end of the spectrum, so keep that in mind.

Now we get to travel the world. The following are a very basic description of what you can expect from certain coffee producing geographies:

- Africa: Acidity and fruit for the most part, but Africa is huge, and their varieties of coffee are plentiful.

Expect to find blueberries from Ethiopia, complex citrus and berry notes coupled with a higher brightness and acidity from Kenya, while richer body, currants, and chocolate can be found from the Burundi/Rwanda area. Again, Africa is huge, so there’s way more out there than mentioned here.

- The Americas: A good balance between body, acidity, and fruit can be found from origins in the Central America region. One of the absolute highlights of that area is the wildly expensive Panamanian Gesha. I remember trying this back in New Zealand a few years ago and it reminded me of tropical Fanta. Truly mindblowing.

Heading further south to Colombia and into Brazil, sweetness and body starts coming to the forefront. Expect more caramel, more chocolate, more nuttiness, and a coffee that is really approachable for a beginner. For a roaster? Brazilian coffee is really hard to get right.

- Asia: A lot of robusta coffee is produced in Asia, but also a fair share of arabica as the market began to shift. From the robusta? Expect more acridity, less aromatics, and a rapidly beating heart. Robusta typically has less caffeine than arabica coffees.

The origin is the best part, in my opinion, of choosing your coffee. This is where we really begin to see the depth and scale of what is available to us from essentially the same product. Things begin to get really crazy when we try the same type of coffee produced in different regions.

So what should you choose? This one is totally up to you. Again, if we have removed the quality of the roaster as a variable, then let your tastebuds guide you. Even easier, ask your roaster for a recommendation. Some of the best coffees I’ve had were way outside my “comfort” zone when it comes to knowing what I like.

What’s next?

That’s it! This is a very high-level breakdown on what you should think about when it comes to choosing your coffee and learning how to approach it as one of the many variables within your coffee making.

As you might have realised, variables within coffee can go into many different levels, and as we look closer and closer, the rabbit-hole doesn’t seem to end. What I recommend is to not get overwhelmed with controlling every iota of the process, but instead develop a more overarching understanding of what is happening and why, and then exploring those avenues more, such as with the origins.

What do you think? Did I miss anything? Do you also get frustrated that all bags of beans don’t have a “Roasted on” date? Let me know in the comments!

Next time I’ll break down more of the brew-level variables and explain how best to manage those, as well as what you can leave to fate.

I actually started writing this with the intent to do all the basics like time, temperature, coffee, method, in one post, but quickly realised I was fooling myself if I thought I could get it all in one spot. There’s so much to uncover in these topics, even when keeping it basic and giving information that you can immediately apply. I almost certainly forgot some things, but no amount of caffeine can wake me up today, so feel free to comment if there’s something you disagree or think I should’ve added!

* Solar flares aren’t a real variable you need to isolate in your brewing.